AustLit

-

"The University of Queensland campus for me, at the age of 17 and as the ‘first in family’ to access higher education was a most daunting place. The campus centrepiece, the Great Court was an imposing spectacle as it towered above me in its sandstone prestige. It was a place I passed by, rather than a place that I could feel at home in. There was however one thing that stood out for me that was vaguely familiar – a carving of an Aboriginal man’s head on the interior walls of the Great Court. Perhaps this acknowledgement of Aboriginality cemented my place in this place I’d thought. Yet it was juxtaposed with numerous carved images of Australia’s flora and fauna.

Frederick Walter Robinson, Professor of English and member of the UQ Grounds Committee described the atmosphere created by the carvings in this space in c.1956:

Some motifs are repeated, but with pleasing variety of arrangement or expression, e.g. the poinsettia, cockatoo, flying-fox, Aboriginal. There is no need to attempt a complete catalogue of subjects—the game is to seek, at any odd moment to identify a few more Australian things which the average Australian does not recognise (cited in Keogh, 2011, 17).

My Aboriginal presence thus is rendered unrecognisable, not only in this place of higher learning, but in my own country. However, our presence on campus today and every day, as Indigenous staff and students powerfully disrupts the meanings of Aboriginality that are inscribed on the buildings of the Great Court."

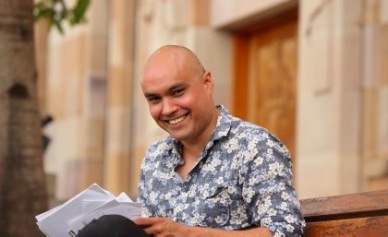

Chelsea Bond – 2014

Dr Chelsea Bond is a Munanjahli and South Sea Islander health researcher and senior lecturer at the University of Queensland’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit.

Keogh, L. (2011) ‘Sandstone Dreams’ Crossroads. Vol V(2): 7-17

-

"I was diagnosed with Endemic Berkits’ Lymphoma in April of 2011. I spent most of that year in the C ward of the Brisbane Private hospital being treated with chemotherapy. The subjected isolation brought insight. I realised that I wanted to become a writer, so I started studies at the University of Queensland in 2012. The Great Court held little significance to me at that time. I was in another white space, however one not as fluorescently lit as my hospital room. It wasn’t until the ‘Courting Blackness’ exhibition in 2014—the last year of my undergraduate studies — that I pondered the difficulties that I had faced in navigating the academic and colonial values that the sandstone campus encompassed.

Being the only Indigenous person in the entire writing cohort, I struggled to find a voice, or I was forced to speak when we encountered racially explicit topics while studying books like Coonardoo (by Katherine Susannah Prichard) and Bitin’ Back (by Vivienne Cleven). The exhibition signified the reclamation of a space both intellectually and geographically; it cast our epistemologies against those of the institution though art—in all its lucid and liminal glory—and helped me understand that my voice was important, especially in that space.

The timing of the exhibition was significant as it influenced the direction of my honours research. I decided that I wanted to look at a great work of Indigenous fiction particularly the rendering of masculine identity. I decided to look at how the male Dreaming figures in Sam Watson’s seminal work The Kadaitcha Sung influenced the masculinities of the male characters, and how these relationships, in a fictional space, could influence Indigenous men in the real world, much as the exhibition had influenced my own path.

Towards the completion of my thesis in 2015, I remember walking through the Great Court. My mind filled with the Dreaming of Watson’s work, I realised that I was also reclaiming that space. Indeed, paradoxically, the very white, traditional, academic merit-based values and form of education that I had struggled with as an undergraduate had opened up the possibility of articulating my own very black history."

Graeme Akhurst – 2016

Graham Akhurst is an Aboriginal writer hailing from the Kokomini of Northern Queensland. He has been published with Mascara Literary Review, and Connect the Dots Journal for fiction, and the Australian Book Review, Cordite, VerityLa, and Off the Coast (Maine America) for poetry. Graham contributed a poem titled “Skin” for an interactive map as part the Brisbane Writers Festival, and has performed readings at the Queensland Poetry Festival, and Clancestry. He was valedictorian of his graduating year and recently completed his writing honours with a first class at the University of Queensland. Graham has ambitions to continue his studies and write his first novel.

-

I remember the Murri and Islander Students Association at UQ tried to get the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags raised on the Forgan-Smith Building’s main flagpoles during NAIDOC week in 1990. The administration wouldn’t let us, but said we could put it up at the security box at the intersection of Sir Fred Schonell Drive and Coldridge St on the other side of the ovals. Talk about out of sight out of mind! Of course they were ripped down the first night by the local racists. This was before the Mabo hysteria of 1993, so it was still very much a white Sir Joh politik in Queensland. We found one flag in the front yard of a nearby house.

So the next year Leonie West and I wrote again to ask it be put up safely on Forgan-Smith. Then they told us it didn’t comply with the Queensland Flags Act and university protocols, and again suggested the security box on the other side of the fields. We did that – at least it wasn’t ripped down this time.

Then in 1992, we asked again, and got support letters from the Murri Unit, academics and community organisations. We told them how it complied with all the regulations, bought special flag cloth material, to their specifications, and they finally let us raise it for the Friday only of NAIDOC Week – to the side of the Australian flag, of course, LOL!

Nowadays it proudly flies all during NAIDOC Week, and that’s to be congratulated. But this shows the whiteness of university institutions, and how they’ll sometimes use their rules at any cost to deny Aboriginal cultural expression and sovereign freedoms. I think when they realised we weren’t going away they kind of capitulated, a little. Nowadays I guess the whiteness in these places just hides elsewhere.

Gregory Phillips – 2014

Gregory Phillips is from the Waanyi and Jaru (Aboriginal Australia) peoples, and comes from Cloncurry and Mount Isa in North-West Queensland. He is a medical anthropologist, has a research master’s degree in medical science, and his thesis, Addictions and Healing in Aboriginal Country was published as a book in 2003. Gregory has worked for twenty years in healing, addictions, youth empowerment, medical education, health workforce and Aboriginal affairs. He developed an accredited Indigenous health curriculum for all medical schools in Australia and New Zealand, founded the Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education Network, and co-wrote a national Indigenous health workforce strategy. He established the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation Ltd in the wake of the federal apology to Indigenous Australians, has advised federal ministers on Indigenous health inequality, and was honoured in 2011 with an ADC Australian Leadership Forum Award.

-

In 1984 I had recently completed my apprenticeship as a sheet-metal worker. For four years I had worked in a factory manufacturing air-conditioning ducts. On a rare day-off from work, I was spending the day following others around and somehow we ended up in the Great Court of the University of Queensland. I guess it was designed to impress, and for me it did make a big impression.

Until that day, I was very happy with my career choice, I was very proud to be a tradesman and spending my days doing hard manual labour. At the time I was living near the beach and I could go surfing before and after work if I wanted to. With a guaranteed weekly pay packet (it was still cash in an envelope back then) I thought I had the best job and lifestyle in the world.

I cannot explain what happened that day in 1984, when I walked into the Great Court, I simply said to myself that one day I am going to go to this university. The next day at 7.00am I was back at work in the factory, thinking ‘I am not going to be working as a sheet-metal worker forever’. I had never thought like that before, I had never thought of going to university before, and most importantly I had no idea how I was going to get accepted into a university considering that fact that I had left high school at the end of the 10th grade with a very average academic record.

Three years later on the first academic day of 1987, I rode my push-bike into the Great Court, chained it up to a bike-rack and nervously headed off to my first lecture. I moved into a share-house in St Lucia with several other students for the next four years I would chain my push-bike up in the Great Court. I never stopped admiring the architecture and always reminded myself how fortunate I was to have the opportunity to be studying at university.

Especially for the first few years, I found university study extremely difficult, especially considering my limited high school education. But I would tell myself, that I had two choices: succeed at university or go back to the sheet-metal factory. So I guess it was not much of a choice. At the end of 1990 I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts with a Double-Major in Anthropology.

Michael Aird – 2014

Michael Aird is an anthropologist, publisher, archivist and curator of Aboriginal cultural heritage who recently curated the Captured exhibition of photography for the Brisbane Museum. http://www.museumofbrisbane.com.au/blog/in-the-spotlight-curator-michael-aird/

You might be interested in...